|

A Thousand Stolen Days

A version of this interview was published in the

third issue of Sublime, which took as its theme

‘freedom’.

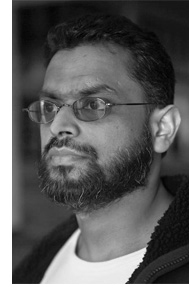

Moazzam

Begg is a small man, but only in physical stature. The

most celebrated of the nine Britons who were held at

Guantánamo Bay, I first encountered him last

year when he spoke to a full house at the East London

Mosque. He talked of his three years in captivity with

intelligence and passion, but also – though he

was aware of only one non-Muslim in the audience –

a remarkable lack of bitterness. In fact, he said he

thanked God for his incarceration. Moazzam

Begg is a small man, but only in physical stature. The

most celebrated of the nine Britons who were held at

Guantánamo Bay, I first encountered him last

year when he spoke to a full house at the East London

Mosque. He talked of his three years in captivity with

intelligence and passion, but also – though he

was aware of only one non-Muslim in the audience –

a remarkable lack of bitterness. In fact, he said he

thanked God for his incarceration.

The title of his autobiography, Enemy Combatant,

is ironic. As a youth he had fought with skinheads on

the streets of Birmingham, and as he grew older and

became more aware of the plight of Muslims in other

parts of the world he had toyed with the idea of joining

the ‘international brigade’ of the Bosnian

army; but though he was excited and inspired by the

idealism of the mujahideen he had met, he realised

he didn’t have the stomach for soldiering.

Instead, in the summer of 2001, he and his Palestinian

wife, Zaynab, went to live in Kabul, to help run a girls’

school that a friend of theirs was planning. He had

already begun to regret this decision when America started

bombing Afghanistan in response to the atrocities of

11 September. Begg and his young family escaped across

the border to the safety of Islamabad – and it

was there that, on 31 January 2002, he was abducted

from his new home at midnight by two badly disguised

Americans and some rather embarrassed Pakistani police.

In a world in which generally only hyperbole gets a

hearing, Begg is surprisingly understated. Irene Khan

of Amnesty International has described Guantánamo

as ‘the gulag of our times’, which is patently

absurd; and the human-rights lawyer Clive Stafford Smith

titled his report on Begg’s captivity ‘One

Thousand Days and Nights of Torture’. Begg himself,

however, makes no such accusations. Indeed, he says

that one of the things that helped him survive his ordeal

was his awareness that around the world many other people

were suffering much more. ‘I used to say to myself,

“Is this as bad as watching your children starve

in Ethiopia? No, it isn’t.”’ And he readily

acknowledges the truth of his captors’ observation,

that in ‘one of your Islamic countries’ he

would have been treated much worse.

Which is not the same as saying, ‘Really, it wasn’t

too bad.’ When I meet him, in a little restaurant

a few hundred yards from Birmingham’s down-at-heel

Central Mosque, he refers to his ‘tormentors’.

It strikes me that the strength of his testimony is

that he speaks quite exactly and does not play with

words. He cites Donald Rumsfeld, who questioned an international

convention on torture: ‘Why is standing limited

to four hours? I stand for eight hours a day.’

Not with a hood over his head, Begg points out, and

his hands cuffed above his head. He seems reluctant

to elaborate on the humiliations and cruelties he had

to endure, but tells me: ‘When I hear the experts

who have written books about Guantánamo, I think:

“You have no idea.”’

In what ways did he suffer most? His answer begins with

the unimaginable and ends with the mundane. ‘The

worst thing was to hear a woman screaming in the cell

next to mine in Bagram [air base]. The interrogators

kept reminding me that I didn’t know what had happened

to Zaynab, and I truly believed it might have been her.

That was the only time I felt real, uncontrollable hate.

I could easily have put my chains round someone’s

neck and strangled them.’

In Guantánamo, where he spent two years in solitary

confinement in a cage measuring eight foot by six, he

says he missed most keenly the freedom to walk more

than three paces in any direction. ‘I missed my

wife, my children’ – his fourth was born while

he was in captivity – ‘I missed the freedom

to pray with other people.’ Then he adds, unexpectedly:

‘One of the things I missed more than anything

was the freedom you feel when you’re driving down

the road with the wind in your face. I missed that greatly.’

Begg’s strengths – his sharp mind, his strong

sense of justice, his evident devotion to his family,

his commitment to a faith that is essentially communal

– could easily have been fatal weaknesses when

shut up alone by a system that seemed to be governed

neither by law nor by reason. How did he cope? He quotes

Nietzsche’s dictum: That which does not kill me

makes me stronger. ‘What I went through has been

very life-shaping, life-changing…’

‘There are examples in the Bible and the Qur’an

of people who used periods of solitude to better themselves,

and I resolved to do the same. I did 200 press-ups and

200 sit-ups a day, and I felt great for it. I could

never have done that as a free man – I never had

the time or the inclination. I learned much of the Qur’an

by heart. I wrote a lot of poetry. I read hundreds of

books, which some of the guards brought me – and

many of them were classics, by Dostoyevsky, Dickens,

the Brontes, which improved my English greatly. I learned

to organise my thoughts. I came to see that time alone

is good time – and a lot of good came out of it

for me.’ He particularly enjoys the irony that

the endless interrogations he was subjected to taught

him to express himself with confidence.

Did he believe his suffering was part of a ‘higher

plan’? ‘Many of the guards told me, “Everything

happens for a reason.” It was the only way they

could make sense of it all. I think they probably believed

in preordination more than I did.’ It was in a

more Stoical idea that he found more consolation. ‘I

used to ask, “Why me?” – until one of

the guards, a Southern Baptist, said to me: “Everyone

asks themselves, ‘Why me, God? Why me?’ But

why not me?”’

Another attitude that helped him was his preference

not to prejudge people. New guards were told in advance

that he was ‘very manipulative, one of the worst

people we have here’; but he found he was able

to make friends with many of the military police who

watched him, and even some of the Marines. One ‘born-again’

soldier admitted to him, ‘I convince myself each

day that you guys are subhuman, so that I can do my

job. We don’t do this to people where I come from.’

When I remind Begg of this, he exclaims: ‘Yes,

but it works both ways. Many people see those who victimise

them as monsters or animals – anything but human.

I didn’t. I just took each person as I found them.

In fact, I enjoyed finding out that some were very different

from what I had expected.’

He refused to accept his captors’ estimation of

him. ‘For me, freedom is a very personal thing.

I always recognised that they can take your liberty

away at any time, but they can’t take the freedom

away that exists within you. And part of that freedom

for me is my dignity, my self-respect, my self-control,

my courtesy.’ These qualities seem to have made

a deep impression on many of his young guards. (It also

helped that, like many of them, he used to watch The

Dukes of Hazzard…) Several of them told him,

‘I’m so glad I came to this place. I’ve

learned so much from you.’ One man ended up crying

on the floor of his cell after confiding that his wife

had left him because he’d committed adultery. Another,

who was ‘as nice as pie’ to Begg, was later

arraigned for beating and threatening to sexually abuse

other prisoners. Begg was taken aback when the man’s

lawyers later contacted him to ask him for a character

reference.

Many of his jailers told him that ‘in a sense’

they were prisoners too, stuck at Guantánamo

against their will. He has little patience with this

– and yet, in a sense, they were far from free.

In their words and actions, as he records them, one

can hear the clink of what William Blake called ‘mind-forg’d

manacles’. The routine that required five shouting

men to shackle him every time he was taken from his

cell smacks of panic rather than prudence. So, too,

do the exhaustive body searches (‘After two years

in solitary confinement, what did they think I might

be concealing?’). When one of his interrogators

pulls his chair away with the words ‘You don’t

deserve to sit when you’re talking to us!’,

it isn’t his victim who is belittled.

‘You’ve seen too many movies,’ he told

his captors more than once, and he shrewdly observes

that they seemed to need to believe that their enemies

were supervillains. Begg, who stands 5 foot 3 in his

bare feet, took a few flying lessons as a teenager,

got a blue belt in tae kwon do and obviously has a gift

for languages; but it still takes an overheated imagination

to see him as some kind of Islamic James Bond. As for

the plan that (he eventually heard at third hand) he

was supposed to have been hatching, to design and build

a pilotless plane and fly it, full of anthrax, into

the Houses of Parliament, well, it might make good cinema

but it doesn’t make sense.

He was finally released on 25 January 2005. He was never

charged, though under duress he signed a ludicrous ‘confession’;

but, like everyone else who has been released from Guantánamo,

he has never received an apology, let alone any compensation.

How difficult did he find it to adjust to being a free

man again? ‘Once I was back in England, it was

almost as if I had never gone. I had been a prisoner

for three years, but prior to that I was a free man

for 33 years. So, I was coming back to that which was

10 times more familiar – that’s how I looked

at it.’ Nonetheless, he has found that now he needs

solitude more than he ever used to before. ‘I spend

most of my time in my house, alone. It’s one effect

of solitary confinement that is going to last for a

very, very long time.’

Has he been able to forgive? ‘I’ve thought

about this a great deal,’ he replies, ‘and

yes, I can forgive; but there must be sincere repentance.

Otherwise, it means nothing. If somebody said, “Moazzam,

what we did to you was bad and I’m sorry for it,”

for me that would be pretty much enough. But if that

person is still doing it to other people…’

What about the two 18-stone FBI men who especially threw

their weight around? ‘If I saw them,’ he says

without hesitation, ‘I’d kick the crap out

of them.’

One thing that still binds him is a feeling of guilt.

‘I visit the relatives of [the four] British residents

who are still held over there – who will never

come back here, because they’re not British citizens

– and I feel very bad. Of all the former detainees,

I speak the most and do the most about their cases,

but to me it’s nowhere near enough and it never

can be. When I see those men’s children, I feel

extremely guilty.’

And if he feels no animosity, does he sense it in others

towards him? ‘People come up to me all the time,

and it’s no exaggeration to say that they always

say something good. I don’t get hostility from

anybody, Muslim or non-Muslim. The support I’ve

received from people, even from Middle Englanders, has

been quite astounding, and quite moving. It’s allowed

me to help to build bridges.’

Moazzam Begg is not a saint or a visionary, but he does

present a challenge. I tell him that at the East London

Mosque, as a succession of impassioned young men had

declared that Muslims must show solidarity with other

Muslims around the world, I had wanted to say that if

we are all to live in peace, what is needed is actually

solidarity between human beings. He looks at me frankly

and says: ‘You should have said it.’

It seems a bit lame to admit that I didn’t have

the courage.

© Sublime 2007

Photograph

© Andrew

Firth

Back to the top

|